Nature-based solutions to keep cities cool in a warming climate

World Green Building Week is the largest global campaign to accelerate climate action in cities. With heatwaves being one of the most concerning consequences of climate change, we explore two scalable prototypes that can be adapted for local conditions to tackle the urban heat island effect.

A healthy city should provide a clean, safe physical environment, an ecosystem that is stable now and sustainable in the long term, and a high degree of participation in and control by its inhabitants over the decisions affecting their lives.

However, with record-breaking temperatures becoming more frequent and intense – the past 10 consecutive years have been the warmest on record – people living in cities are increasingly exposed to heatwaves, over which they have no control. There is an increase in heat-related morbidity and mortality on all continents, which places an unprecedented burden on public health services.

With more than half the world's population living in urban areas, and these heatwaves having such a severe impact on the physical health and mental well-being of people, a call for urgent targeted interventions and adaptation measures is necessary.

Urban heat islands

Urban heat islands (UHIs) occur when urban environments with dense infrastructure are significantly warmer than the surrounding suburban and rural areas. This phenomenon is usually most noticeable overnight, when the temperature difference can be as much as 12°C between the inner city and surrounding countryside.

Factors contributing to the UHI effect

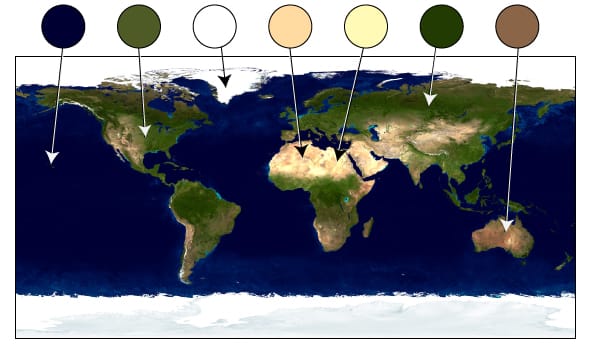

Dark surfaces tend to absorb more solar radiation during the day and heat up quicker than the countryside. This heat is then released into the city air, creating a warming effect. With higher levels of particles and pollutants, this air is more capable of holding onto the heat, whereas in the countryside, where the air is usually clearer, more of that heat can pass through the atmosphere.

As well as the heat-retention properties of materials like concrete and asphalt, and the heat generated from vehicles, industrial processes, and air conditioning, the topography of urban areas adds to the UHI effect.

Urban canyons are created when a narrow street is flanked by continuous buildings, especially skyscrapers, on both sides. The modification of the characteristics of the atmospheric boundary layer within the canyon is called the urban canyon effect.

Urban canyons affect various local conditions, including wind speed and direction due to the buildings creating more friction to the flow. This reduces the wind's ability to disperse heat, which in turn contributes to the UHI effect. Temperature inside the canyon can be elevated by as much as 4°C.

Cities also have less vegetation than rural areas. And less greenery means less evaporation, which plays a crucial role in maintaining moisture levels in the environment and regulating temperature.

When sunlight hits pale coloured surfaces, much of it is reflected, bouncing back out to space. When sunlight hits dark coloured surfaces, most of it is absorbed. The amount of energy reflected by a surface is called albedo. Surfaces with dark colours have an albedo close to zero. Surfaces with pale colours have an albedo close to 100%. Forests have an albedo of about 15%, while snow has an albedo of 90%.

Although cities consume 78% of the world’s energy and produce more than 60% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, they account for less than 2% of the Earth’s surface. The difference in surface albedo between urban and rural areas is a major contributor to the differences in temperatures between the two locations.

Integrating and enhancing green and blue infrastructure (vegetation and water features) to increase the albedo of surfaces in urban areas is one of the most effective measures to counteract the UHI effect.

Trees as allies in the mitigation of climate change

Through a process called evapotranspiration (evaporation + transpiration), trees help cool the air. During transpiration, water from the soil is absorbed by the tree's roots and transported to the leaves. This process requires energy, which is absorbed from the heat in the surrounding air. The water then exits through tiny pores on the leaf’s surface where it evaporates into the atmosphere. This process of evaporation – changing water from a liquid to vapour – also requires energy, which is absorbed from the heat in the surrounding air.

A mature tree can transpire up to 150 litres of water per day. In a hot, dry location such as Perth in Australia, this produces a cooling effect equivalent to that of two air conditioners running for 20 hours.

The problem with large-scale tree plantation programmes

In recent years, there has been a growing clamour to repopulate the trillions of trees our planet has lost over the centuries. Unfortunately, large-scale tree plantation programmes are not usually an efficient or effective solution because most of the time they choose monocultures, i.e. only one species, which store less carbon, are terrible for biodiversity, and are also highly susceptible to disease.

Below, we'll explore two of the world's most successful urban greening projects – the first a building, the second a city – both scalable prototypes that can be adapted to local conditions, to create the kind of resilient, low-carbon, and inclusive urban environments we all deserve.

Success Story 1: Milan's Vertical Forest

With 3.16 million inhabitants (2024), Milan’s metro area is one of the most densely populated and industrialised regions in Italy, and Europe, and it suffers from a pronounced UHI effect, one of the worst on the continent.

Only 13% of the city is green spaces, compared to more than 30% in Rome. The Alps also form a natural barrier that protects the city from major air circulations coming from the north, so the discomfort from the intense heat and humidity can be exacerbated by the lack of wind.

The green curtain effect

Born out of architect Stefano Boeri’s aversion to what he calls ‘mineral cities’ and the inhospitable environment they create, he set about designing Milan’s first biological and sustainable tower, clad not in light-reflecting and heat-generating materials like metal and ceramics and glass, but rather a lush curtain of foliage.

The resulting Bosco Verticale (Vertical Forest) has become one of the world's most recognisable examples of green urban living. The most distinctive feature of the twin apartment blocks which stand tall in the city’s Porta Nuova district are the living facades, clad in a curated selection of more than 90 species of trees and shrubs and plants.

The residential high-rises boast a combined total of 800 trees, 5,000 shrubs, and 15,000 perennials and/or ground-covering plants. This provides vegetation equivalent to 30,000 sq. m of woodland and undergrowth, which converts around 20,000 kg of carbon each year.

The plant-based shield regulates humidity, produces oxygen, absorbs CO2 and microparticles, and helps moderate temperatures in the building during summer by filtering direct sunlight and shading the interiors. The buildings also use heat pump technology to reduce cooling costs and emissions.

Meticulous planning & foresight to avoid costly mistakes

The development of the botanical component was the result of three years of studies conducted together with a group of botanists and ethologists before construction of the building even began. Because planting the wrong species of tree, in the wrong type of soil, in the wrong location is a recipe for failure and a waste of valuable resources.

The choice and distribution of the plants and trees reflect both aesthetic and functional criteria applied in relation to the direction and heights of the facades. And the plants destined to be installed in the towers were cultivated in a special botanical nursery at a garden centre near Como to get them used to living in conditions similar to those found in their eventual homes.

Tended by technology & a team of flying gardeners

Structurally, the towers are characterised by large, staggered, and overhanging balconies, each about three metres wide, to accommodate large external tubs for vegetation, and allow for the unhindered growth of larger trees, up to three storeys high.

All the maintenance and greening operations are managed at a centralised condominium level. The day-to-day needs of the plants are monitored by a digitally and remotely controlled drip irrigation system and watered only as needed, using filtered greywater produced by the building.

However, every few months, the big guns are called in to ensure the health and maintenance of all the trees and vegetation on each floor. Known as the Flying Gardeners, this highly specialised team of expert arboriculturists uses advanced mountaineering techniques to descend from the building’s rooftop and attend to all the necessary trimming and pruning. They also check the state of the plants to identify any needing removal or substitution.

A solution to urban sprawl provides a cosy home for wildlife

A few years after its construction, the Vertical Forest had established itself as a thriving example of spontaneous flora and fauna recolonisation in the city, providing a habitat for around 1,600 species of birds and butterflies.

This innovative project paves the way for a new era of architectural biodiversity, with metropolitan reforestation and vertical greening providing a solution to urban sprawl, and enhancing sustainability by reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions, whilst helping to cool the air and combat the UHI effect.

Success Story 2: Medellín's Green Corridors

Medellín, with a metro area population of 4.137 million (2024), is Colombia's second largest city after Bogotá. And its urban planners have been nurturing an architectural uprising, culminating in two international awards for its hugely successful Green Corridors project.

Supported by funding from a municipal participatory budget, the project involved laying down 30 Green Corridors across the city, connecting newly-greened road verges, vertical gardens, streams, parks, and nearby hills.

Average air temperatures in corridors dropped 4.5°C

The planting of almost 880,000 trees and 2.5 million smaller plants has helped the city achieve significant heat reductions. From 2016 to 2019, average air temperatures in the city’s Green Corridors fell from 31.6°C to 27.1°C, and average surface temperatures dropped by over 10 degrees, from 40.5°C to 30.2°C.

Enhanced biodiversity helps with pest control

As well as cooling built-up areas, these Green Corridors pump oxygen back into the air, absorb dust and pollutants, insulate noise, and promote biodiversity of animal species. Monitoring of local wildlife has seen birds, lizards, frogs, and bats in the corridor. Locals believe this has helped keep rats and other pests under control.

Health benefits of cleaner air & cooler roads

Due to a significant improvement in air quality, the city’s morbidity rate from acute respiratory infections fell from 159.8 per thousand inhabitants to 95.3 over the same three-year period.

And thanks to the welcome canopy of shade provided by trees for pedestrians and cyclists, the city saw a 34.6% surge in cycling, aided by the construction of 80 km of new bike paths as part of the project.

Job creation for disadvantaged communities

The project also brought training and employment opportunities, with 107 people from disadvantaged communities trained as city gardeners and planting technicians, and 2,600 jobs created. A programme was also set up to help people arriving in Medellín after being displaced by armed conflict in Colombia find permanent jobs maintaining the Green Corridors.

Targeting the busiest areas for the greatest impact, every aspect of the programme – from lower temperatures and better health to job creation – has driven progress towards a fairer, more equal city, with people of all ages and from diverse economic backgrounds able to come together and enjoy its 1.5 million sq. m of public green space.