Quarterly International Carbon Update: Q2 2025

Stabilising climate change requires robust plans, not just rhetoric. Countries need strong leadership and decisive action. 2030 is now just four-and-a-half years away, and if governments fail to meet national net zero targets, they could face significant financial penalties or other indirect costs.

The majority of countries around the world have set targets for reaching net zero emissions on timescales compatible with the Paris Agreement (2015) temperature goals. In this, the second edition of our spotlight series on global decarbonisation efforts, we take a closer look at how different parties are measuring up, and the potential costs for countries that fail to meet their 2030 targets.

Latest predictions

The latest Global Annual to Decadal Climate Update from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) projects that temperatures will continue rising during the 2025–2029 period.

WMO forecasts an 80% chance that a new annual heat record will be set, and a 70% chance that the five-year average will exceed the critical 1.5°C warming threshold outlined in the Paris Agreement. This ongoing increase in global mean temperatures, primarily driven by human activities and amplified by natural phenomena like El Niño, is expected to exacerbate impacts on societies, economies, and ecosystems.

In order to stabilise climate change, economies are challenged with reaching a global peaking of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as soon as possible, with an emissions reduction of 45% by 2030, and achieving net zero by 2050.

Net zero vs carbon neutral – what’s the difference?

While both terms relate to balancing GHG emissions, ‘net zero’ and ‘carbon neutral’ are not interchangeable. Net zero refers to balancing all GHGs – including carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and fluorinated gases – with removal from the atmosphere, while carbon neutral typically focuses on balancing CO2 emissions through reductions and offsets.

In essence, net zero is a more comprehensive and ambitious goal that requires a deeper transformation towards a low-carbon economy, while carbon neutrality can be a stepping stone towards achieving net zero or a way to mitigate the impact of emissions.

So, who’s moving towards net zero?

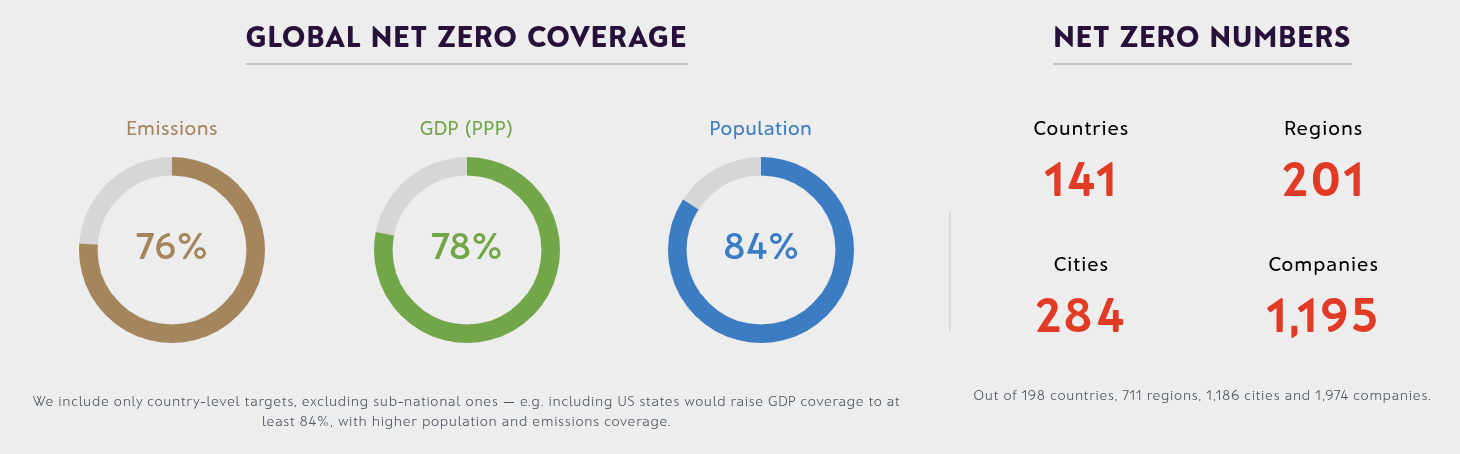

In 2024, net zero targets were in place in nations accounting for 93% of global GDP. With the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement (in 2025), but factoring in those US states with their own targets, that number has now fallen to 84%. This currently covers three-quarters of global emissions, and 84% of the world’s population.

How does the Paris Agreement hold member countries accountable?

All member countries are required to make pledges of action every five years to lower their GHG emissions, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). While countries must submit these pledges, the specific content of the NDCs is determined by each member country (a topic we covered extensively in our previous Carbon Update).

The primary focus of accountability is on accurate reporting. Every member country must send periodic reports detailing their national emissions inventories and their progress towards achieving their NDCs. If a country fails to meet its targets, the main formal consequence is a meeting with a global committee of neutral researchers. This committee then works with the struggling member country to develop new plans.

While the Paris Agreement itself does not impose hard financial penalties, the European Union (EU) and some other jurisdictions have established their own compliance frameworks.

Penalties for EU Member States party to the Paris Agreement

If EU Member States fail to meet their net zero targets by 2030, they will likely face financial penalties, primarily through the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) and related legislation.

The ESR establishes binding national targets for emissions reductions in sectors not covered by the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), such as agriculture, buildings, and transport. Targets are set according to a country’s relative wealth (GDP per capita), and some other adjusting criteria. This means countries like Denmark, Germany, and Luxembourg have much higher responsibilities than, for example, Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia.

While most Member States are at risk of missing their ESR targets, the financial burden varies. Germany, France, and Italy face large emissions gaps. This could result in significant costs. However, as a share of their economies, these costs are relatively low, at around 0.2% of GDP.

For smaller countries like Ireland, the costs are much higher when assessed as a percentage of gross national income (GNI). Projections suggest penalties ranging from €7.5 billion to €26.4 billion if it doesn't meet its ESR targets for the period up to 2030. This can significantly impact public finances, putting a massive strain on the national budget, and potentially diverting funds from other essential services.

Penalties for non-EU countries party to the Paris Agreement

While non-EU countries party to the Paris Agreement do not face direct financial penalties, they may encounter other forms of indirect costs, such as loss of access to climate finance, reputational damage, or trade measures (e.g. carbon border adjustments).

Available options to offset risks

Financial penalties for Member States exceeding their emissions caps are not straightforward fines, but rather costs associated with ‘buying compliance’.

Option 1: Purchasing emissions allowances from other Member States

For EU Member States, emissions allowances are calculated based on a combination of factors, including historical emissions, specific sector characteristics, and the overall EU-wide emissions reduction targets.

Member States that outperform their annual targets can auction off their surplus allowances to other Member States that face emissions gaps and are at risk of missing their ESR targets. Since 2013, auctioning has been the default method for distributing emissions allowances in the EU ETS. This approach implements the 'polluter pays' principle, ensuring that those who emit pollutants pay for the right to do so.

However, when you consider that shortfalls expected for three large Member States – Germany, France, and Italy – could be substantial, and the fact that Germany’s expected shortfall might require more than half of the emissions allowances likely to be available, a shortage of allocations could result in a bidding war. This is a scenario that smaller Member States want to avoid.

Option 2: Contributing to a climate fund

Contributing to a climate fund that provides financial and technological support for developing countries to meet their NDCs is an alternative to purchasing emissions allowances.

Funds are typically transferred through existing channels, such as United Nations (UN) programmes or individual countries' foreign aid offices. The UN has also established central channels for aid distribution, including the Green Climate Fund and the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Both have their own accounting mechanisms to track and audit the funding they disburse.

Whole-of-government, whole-of-society approach

The journey ahead requires robust plans, not just rhetoric. Countries need strong leadership and decisive action.

Governments must prioritise the acceleration and scaling of decarbonisation efforts as a matter of urgency. The focus needs to shift towards the immediate implementation of policies that have already been approved but not yet enacted. And civil society needs to hold those in positions of power accountable.

2030 is now just four-and-a-half years away, and national targets will need to be met. Every euro spent on buying compliance is a euro not spent on education, healthcare, housing, or transport.